Baltimore County is currently soliciting public input on the development of its 2030 Master Plan. To those of us reeling from recent ad hoc zoning decisions, putting parochial interests and the desires of developers ahead of the common good, that is a hopeful sign. A good master plan should guide development and lessen such shenanigans. In the words of NeighborSpace Board Chair, Klaus Philipsen, “a good [master] plan is an essential tool for fighting bad development” for “directing development is like directing water: Easier done upstream than downstream …. A 10-year plan should be used as a manual which planners, citizens and stakeholders use to hold the executive and legislative branches accountable.” K. Philipsen. “What Makes a Good Comprehensive Plan?” Community Architect. July 2021 (Available at: http://archplanbaltimore.blogspot.com/2021/07/what-makes-good-comprehensive-plan.html)

1. THE PRESSING NEED FOR A GOOD PLAN

A good plan is essential for us now because the choices the County has made around development and land use inside the URDL in the last 50 years have been something less than visionary. There is plenty of well-worn data to back that up:

- 65% of residences lack access to adequate open space within a ¼ mile walk;

- None of our inner suburbs are considered walkable, according to the website, walkscore.com, a result that impacts the health of our families and the value of our homes;

- All but one of the 14 county watersheds are impaired by sediment and/or nutrients, impacting water quality;

- The vast majority of our housing stock is old, with home values not keeping pace with surrounding counties, making Baltimore County less desirable than neighboring jurisdictions as a place to live. (For more on this history, see the About Page of the NeighborSpace website and/or listen to this short podcast).

2. EMBRACING EQUITABLE GROWTH IN THE PLAN: WE THE PEOPLE

Many of these facts are recounted in We the People, an equitable growth white paper prepared by Nicholas Stewart, a lawyer from Catonsville and former member of the County School Board, and Pat Keller, a planner from Perry Hall and a former director of the Baltimore County Planning Department. They believe that we should “[u]se the Master Plan 2030 process to create an actionable “equitable growth” strategy that helps address the above challenges, by building consensus on future development and preventing highly charged project-level conflicts down the road.” We the People, p. 3. The ultimate goal of this strategy is to “create a predictable and transparent development process so that the county can reinvent the suburbs and create attractive, livable and sustainable complete communities with decent, affordable housing options for all.” We the People, p. 3.

Stewart and Keller offer specific solutions in support of their equitable growth goal, among them:

- Master Plan as Controlling Document: “The county should transform the Master Plan from an aspirational document that can be ignored by decision-makers (including councilmembers) at their discretion into a controlling document that governs future map amendments.”

- Mixed-Use Development: “With its abundance of underinvested first-tier suburbs – which do not have the amenities of complete communities and are unconnected to one another – Baltimore County is poised to reap significant benefits from well-planned, mixed-used developments. The county must make it easier to develop high-quality projects.”

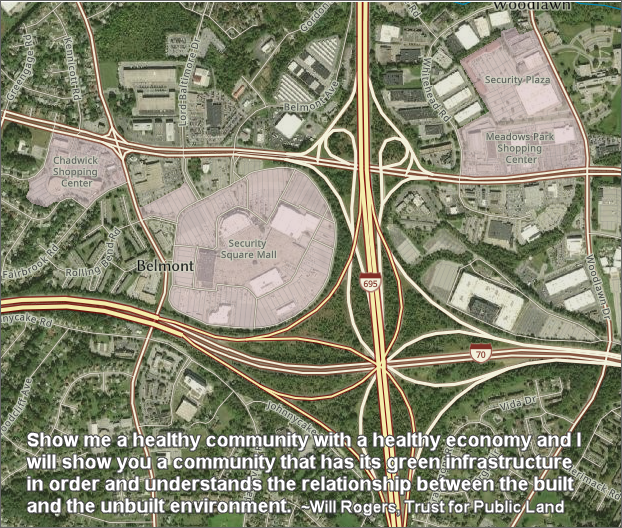

- Green Infrastructure Network: “The county should establish a Green Infrastructure Network so that it can improve the connectivity among green hubs, and thereby make the most of the open space, parks, trails and greenways that currently exist.”

- Simpler, Better Zoning Laws, Regulations and Processes:

- Wholesale review of zoning laws, regulations and processes to simplify them where possible.

- Reform or replace the “planned unit development” or “PUD” process, which is the primary tool to develop mixed-use projects (including limits on density increases).

- Require zoning bills to have a 90-day period of review and comment by the Planning Department and the Planning Board, after which the council may proceed with a vote.

- Require zoning amendments to have a 30-day review period (council cannot propose such amendments and vote on them at the same meeting). We the People, p. 4

3. PRECEDENT FROM SIMILAR PLACES

The strategies seem like straightforward ideas that would go a long way toward addressing the challenges recounted earlier. More than that, they are the very solutions that are being implemented currently in other inner suburbs, places with whom we share a common historical pattern of development and related challenges, around the country. Let’s look at a few examples:

A. Sandy Springs, Georgia

Future growth will largely, and by necessity, occur in the form of redevelopment, with new land uses replacing aging and underutilized buildings, shopping centers, and parking lots. Meanwhile, land use decisions will require balancing growth with other priorities: the desire to maintain the city’s green character and tree canopy, protect neighborhoods, and conserve land for parks, recreation and green space. Sandy Springs Comprehensive Plan (2017), p. 41

Sandy Springs also shares our walkability challenges. The 2017 Master Plan notes that:

Existing development patterns reflect an emphasis, and reliance, on automobile travel, as the city has been designed to accommodate our vehicles …. However, redevelopment opportunities present a related opportunity to rethink mobility by restructuring the physical form of the city and its land use patterns to support a more connected network and greater range of transportation options, including walking, bicycling and transit. Sandy Springs Comprehensive Plan (2017), p. 44.

Finally, while arguably not as challenged as Baltimore County when it comes to open space, Sandy Springs falls well below the median when it comes to acres of parkland per 1000 residents. The master plan notes that:

[N]atural assets play a significant role in defining the city’s character. Although Sandy Springs made strides in preserving natural areas, the City requires a larger-scale plan to preserve existing green spaces, views, the river and streams, and the tree canopy, especially as growth pressures increase. Sandy Springs Comprehensive Plan (2017), p. 60.

The Sandy Springs master plan answers these challenges with the following proposed strategies:

- "Create a new Sandy Springs Development Code that will define the expectations and standards for achieving high-quality development through a process that is orderly, predictable, clear and reliable, and that will focus on the protection of Sandy Springs’ neighborhoods."

- "Develop an expanded trail network to connect neighborhoods to green spaces and natural areas, and fund construction of at least one footbridge across the Chattahoochee River."

- "Enhance and beautify the City’s public places, including its streets and open/green spaces, through the generous use of canopy trees, landscaping, flower displays, public art and attractive signage, to provide vibrancy to these places and as a demonstration of city pride and “sense of place.”" Sandy Springs Comprehensive Plan (2017), p. 72

Subsequent to development of its 2017 master plan, the city developed a Trail Master Plan in 2019. Central to being able to realize the goals of these plans is a mandatory impact fee for public parks and recreation that is part of its subdivision ordinance.

B. Vancouver, Washington

Like Baltimore County, Vancouver also has areas where there are food deserts and a growing contingent of persons aged 65 and older. Though not entirely built out, Vancouver intends to accommodate a substantial amount of growth through redevelopment and development of underutilized lands.

All of these challenges are addressed in master plan policy statements as follows:

- “Infill and redevelopment: Where compatible with surrounding uses, efficiently use urban land by facilitating infill of undeveloped properties, and redevelopment of underutilized and developed properties. Allow for conversion of single to multi-family housing where designed to be compatible with surrounding uses.”

- “Neighborhood livability: Maintain and facilitate development of stable, multi-use neighborhoods that contain a compatible mix of housing, jobs, stores, and open and public spaces in a wellplanned, safe pedestrian environment.”

- “Human scale, accessible development, and interaction: Facilitate development that is human scale and encourages pedestrian use and human interaction.”

- “Connected and integrated communities: Facilitate the development of complete neighborhoods and subareas containing stores, restaurants, parks and public facilities, and other amenities used by local residents.”

- “Public Health and the built environment: Promote improved public health through measures including but not limited to the following: (a) Develop integrated land use and street patterns, sidewalk and recreational facilities that encourage walking or biking (b) Recruit and retain supermarkets and other stores serving fresh food in areas otherwise lacking them (c) Assess and promote opportunities for growing food in home or community gardens, with particular emphasis on areas in the vicinity of multi-family or smaller lot single family housing.”

- “Aging Populations: Update policies, standards, and practices as necessary to accommodate anticipated aging of the local population.” City of Vancouver Comprehensive Plan 2011-2030, p. 1-14, 1-15.

The parks and open space policies quoted above are supported by an ordinance requiring all development to pay a park impact fee.

While this plan is somewhat dated (and currently in process of being revised), there is evidence to suggest it has had its intended effect. The City has achieved high rankings on livability of late. The website Livability.com ranked Vancouver #37 on its list of the top 100 best places to live in 2019. Another website offering livability rankings, Areavibes, gave Vancouver a livability score of 71 out of 100, a result deemed “excellent” on its scoring metric.

C. Lower Merion Township, Pennsylvania

Lower Merion Township embodies the unique physical characteristics and planning challenges of inner-ring, commuter suburbs. The Township has a physical and social connection to the City of Philadelphia as evidenced by the transportation infrastructure and by the number of Township residents who regularly visit the City …. Conversely, Lower Merion Township was historically developed as a distinct political subdivision and suburban community apart from the City of Philadelphia. A large degree of the Township’s identity is derived from functioning as a low density, suburban greenbelt on the western edge of a major urban center. Future municipal planning efforts and land use policies should carefully balance the dynamics required to remain a functionally integrated suburb of Philadelphia without becoming urbanized. From a land planning perspective, this goal may be accomplished by maintaining the Township’s high quality, low density, suburban character and recognizing and addressing gradual shifts towards urbanization within the Township.

The ongoing development pressure and the continued need to address urban externalities, such as crime, traffic, and failing public schools in the city, is an issue common to all inner-ring suburbs. Recent employment and housing data indicates a revival of Center City Philadelphia and its adjacent residential neighborhoods after a half century of decline. The economic and social health of Philadelphia directly impacts the City’s inner-ring suburbs. Lower Merion Comprehensive Plan 2016, p. 151

Like Baltimore County, Lower Merion is substantially built out, neighborhoods are disconnected from other uses, and open space is in high demand. The plan includes recommendations to modify the zoning regulations to maintain the existing character of established neighborhoods, while also encouraging appropriately scaled infill and mixed-use development near transit and shopping. Lower Merion Comprehensive Plan 2016. With respect to parks and open space, the plan recommends:

- Exploration of creative means to uncover the potential of overlooked or underutilized areas as valuable open spaces.

- Installation of sidewalks in established parts of the Township to provide linkages between residential neighborhoods and open spaces while also addressing resident concerns.

- Exploration of alternative uses for underutilized passive recreation areas.

- Continued partnerships with nonprofits to preserve and maintain open space. Lower Merion Comprehensive Plan Issues, pp. 165-168

The open space and recreation provisions are supported by an ordinance requiring the dedication of land or payment of a fee in lieu thereof in connection with subdivision development. The Township also advocates revisions to conventional zoning codes, preservation, and form-based zoning as the primary tools for achieving its master plan goals.

4. THE UPSHOT

Stewart and Keller are right: Master Plan 2030 presents a fabulous opportunity to once and for all get a handle on development so that we can begin to ensure that all communities inside the URDL are livable. The fact that other jurisdictions around the country with a historical pattern of development like our own have already adopted the strategies for which they advocate should alert us to the urgency surrounding their inclusion in the 2030 plan. The fact that subdivision ordinances require developers to do their fair share by either providing public space or paying a fee in lieu thereof is also something that should drive our reconsideration of the shortsighted way in which we handle that same issue presently in Baltimore County.

Stewart and Keller will speak about We the People at the next meeting of the Baltimore County Green Alliance on September 30 at 6:30 PM. Anyone who is a member of a BCGA organization, including donors to NeighborSpace, is welcome to attend and participate in the discussion. You can register here.