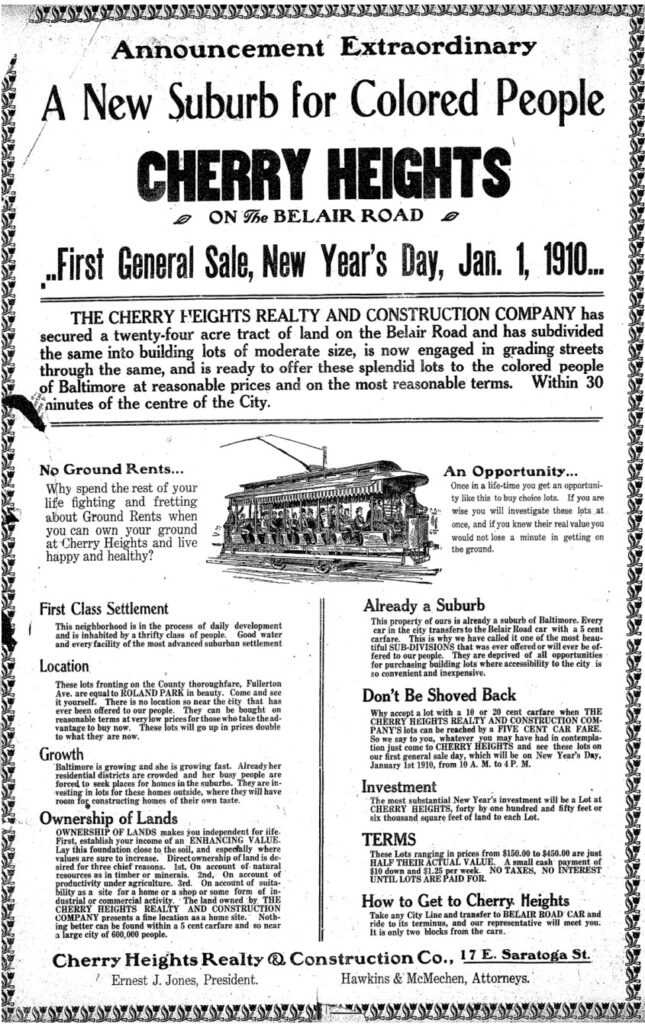

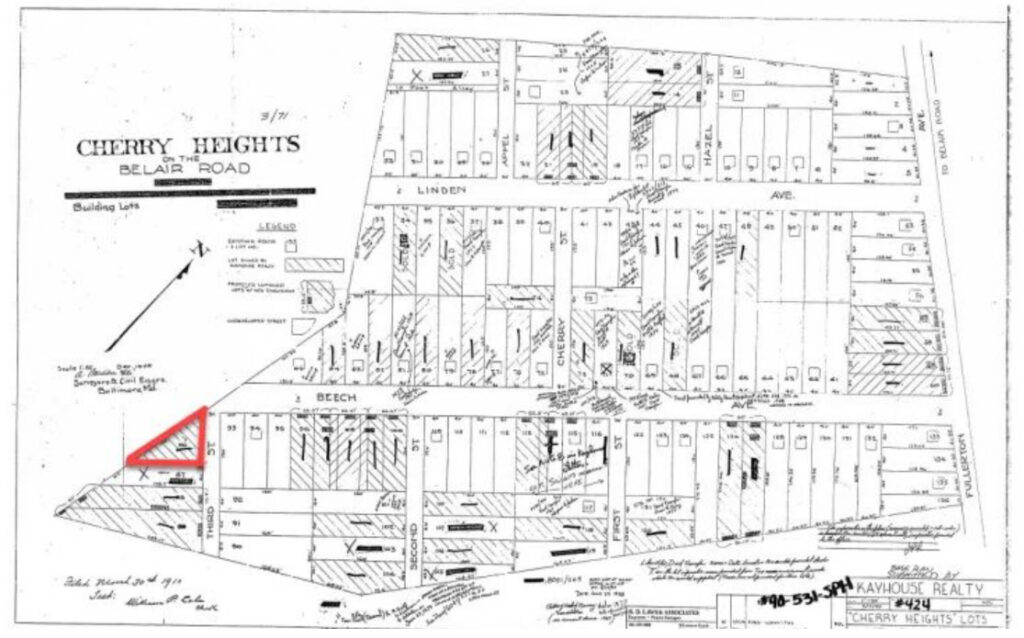

On January 11th, Towson University Associate Professor Dr. Sya Buryn Kedzior and students Ja’lyn Hicks and Collin Bates presented their team’s findings on the history of the Cherry Heights neighborhood in Overlea. NeighborSpace has a small park there named Cherry Heights Woodland Garden after the former African-American community of Cherry Heights whose boundary runs diagonally through the property. According to the report, the community plan was drawn up in 1909, “developed and marketed as the first community for African American homeowners in Baltimore County.”

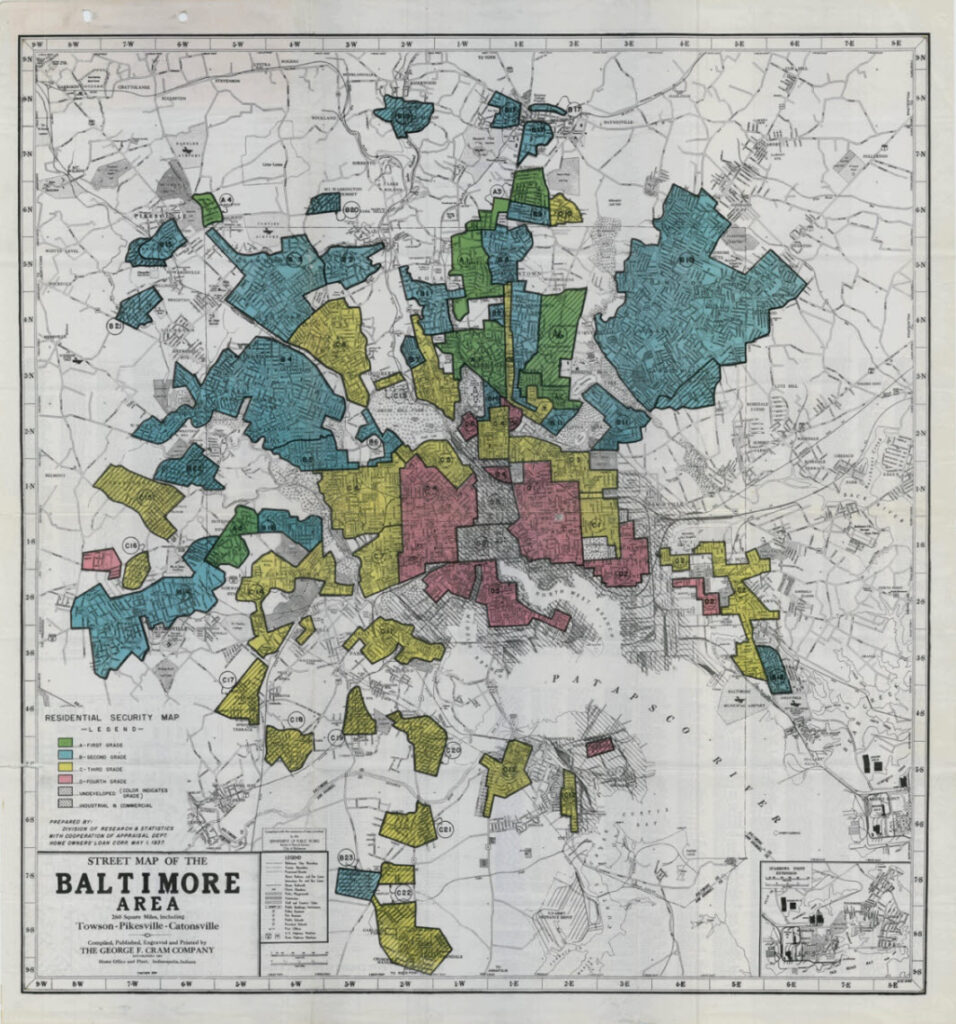

Included in the report itself are sections outlining the early development of and pushback against the neighborhood; a history of the practices of urban planning and redlining in the greater Baltimore metropolitan area; descriptions of the various methods of segregation used by county officials and unsupportive residents to slow the growth of the Cherry Heights neighborhood and others like it; a survey of census data on the neighborhood’s demographics; and a discussion of the neighborhood’s most important landmarks and prominent residents.

The Towson University team presented their findings to an engaged and enthusiastic crowd, including neighbors, local residents, District 6 County Councilman Mike Ertel, and NeighborSpace Board and staff members. As part of the presentation, the team shared some additional context and information. For one thing, there was a shift in how the community lots were marketed and used over time. They were originally marketed to affluent African-Americans as bucolic plots “in the country” to later build a home on for retirement, which can be seen in the restrictions on building materials that could be used and the fact that many people bought lots but didn’t build until much later (or not at all). Over 20 years or so, the neighborhood shifted to an area where people lived year-round. Density also changed: plots were originally marketed for single-family homes but census records show that many residences were duplexes and apartments. Throughout this shift, the importance of the streetcar cannot be overstated. While Black residents lived in Cherry Heights, they still worked, worshipped and were forced to go to school in the City. This transportation was crucial to the vitality of Cherry Heights.

There is still much to be uncovered about the neighborhood. The researchers had to rely predominantly on written records and resources, but more could be learned from first-hand accounts by older residents or from primary sources still existing within the community. At the presentation, a few attendees who still live in the area spoke of historical documents that had been passed down to them – one mentioned having the original deed to their home which included racially restrictive covenants (a common practice at the time}, and another found documents going back to W. Ashbie Hawkins (mentioned first on pg. 9 of the report). Another difficulty to historical research is that, as Dr. Kedzior put it, “often what is normalized isn’t documented.” While it is well-documented that the community association was active in hosting events and advocating for schools, there is less information about the activities of the local churches, even though they were just as pivotal to the community culture. What was their attendance like? What activities did they host? What was their involvement in the community politics? As such information would have been common knowledge locally at the time, there is not a clear record, and therefore room for further discoveries about the neighborhood.

We would like to thank Dr. Kedzior, Ja’lyn Hicks, Collin Bates, Shepsura Page, and Tyler Roberts for all of their hard work on this research and presentation. Though we unfortunately do not have a recording of the presentation, if you would like to read the report for yourself, the final draft and appendices are linked on our website here.