Invasive species continue to be an ecological concern because of their ability to outcompete native species for resources. At NeighborSpace, we dedicate significant time and resources to managing invasive terrestrial plants as one aspect of supporting biodiversity and healthy ecosystems in our parks.

Within the last decade, scientists, land managers, government agencies, gardeners, horticultural nurseries, and others have rallied around native plants. Organizations offer training programs to help professionals and volunteers learn to identify and remove invasive species. Laws have been passed to regulate the selling and use of invasives. Just this month, Maryland signed The Biodiversity and Agriculture Protection Act (HB979/SB915) which bans the sale of harmful invasive species.

Some involved in the study and management of invasive species have begun to question some of the language used to describe invasives, arguing that much of the rhetoric has roots in political and militaristic language. The term “invasive” is, for example, also used often in the context of war, as in an invasion or occupation at geopolitical borders. Other language used to describe the threat and management of invasive species includes: eradication, enemy, sneaking over borders, crossing borders, hitchhikers, and weed warriors.

Instead of using language associated with the human-made constructs of war, politics, and national boundaries, some have proposed shifting to ecosystem-based language around invasive species.

For example, instead of the common name Asian carp for the fish species, Cyprinus carpio can instead be called invasive carp or broadhead carp. This name change was, in fact, signed into law in Minnesota in 2014. The Minnesota law states that: The commissioner of natural resources shall not propose laws to the legislature that contain the term “Asian carp.” The commissioner shall use the term “invasive carp” or refer to the specific species in any proposed laws, rules, or official documents when referring to carp species that are not naturalized to the waters of this state.

This change is in line with a desire to move away from human-centric, place-based names and towards names that are ecologically descriptive. Celastrus orbiculatus (oriental bittersweet), for example, can be referred to as roundleaf bittersweet, named such because its leaves are rounder than American bittersweet. This renaming has the added advantage of a descriptive component (roundleaf) that can support accurate field identification, especially for commonly confused species.

The entomology community was the first to start this work, in its consideration of the renaming of gypsy moths. Advocates for name changes wanted to move away from names associated with groups of people or nationalities, considering the connotations of pairing the term invasive with words used to identify groups of people. Derogatory terms, such as gypsy or oriental are especially problematic, as are those naming conventions that negatively impact BIPOC and immigrant communities. Gypsy is a racial slur that has been used to refer to the Romani people. The Entomological Society of America (ESA), which controls common names for insects, announced in 2022 that the Lymantria dispar would henceforth have the common name spongy moth. You can read more about the ESA’s efforts here, as well as their working group: the Better Common Names Project.

University of Minnesota Extension has also been a leader in this effort, forming a working group and process for reconsidering common names. This working group addressed the renaming of invasive Asian jumping worms, as well as other jumping worm species. Their efforts focused on renaming conventions that more closely follow the scientific names or descriptive names that align with the species’ physiological characteristics, behavior, or other identifying and distinguishing features. Read more about the University of Minnesota Extension’s Guiding Principles “to inform selecting primary common names for new non-native species”.

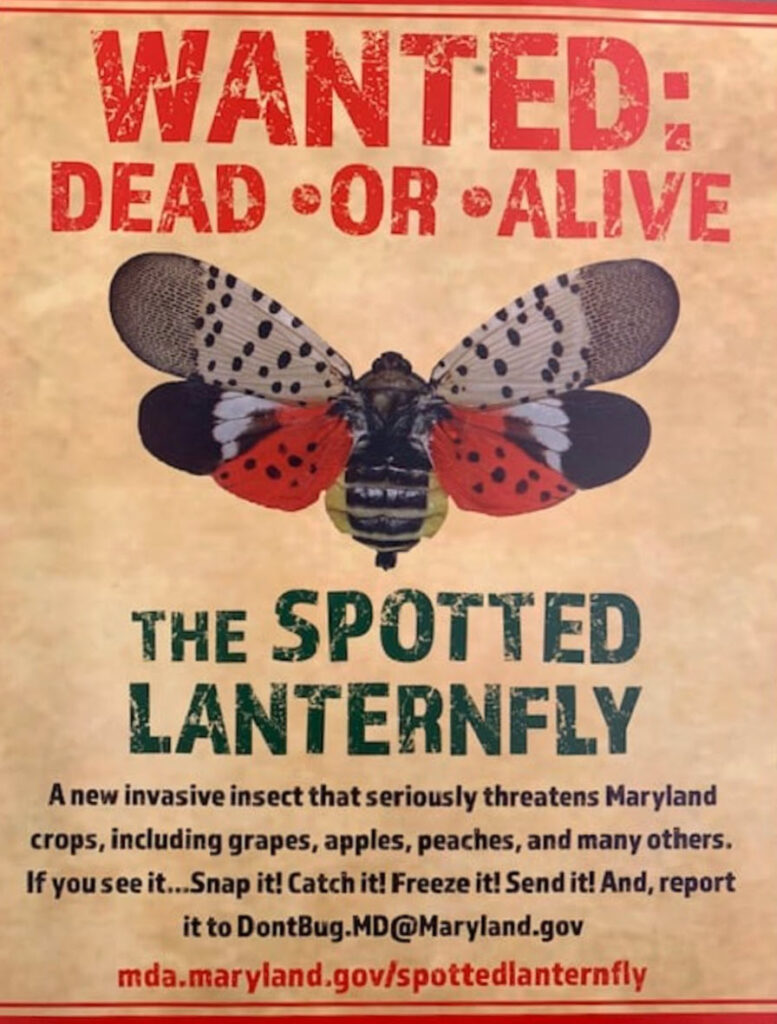

Much of this work stemmed from a desire to reduce the harmful impacts of naming conventions that are associated with groups of people, places, and geopolitical boundaries. There are also conversations about trying to move away from overly moralistic language about invasive species, which are often pitted against native species in a good versus evil narrative. Campaigns, news headlines, and volunteer recruitment posters about invasive species management have anthropomorphized living organisms, casting them in a villainous or monster role. Plants, of course, do not have morality; this is a human construct.

Additionally, language around needing to save good native plants from the bad invasive ones can make native plants seem passive, like they need to be rescued and are unable on their own to adapt for survival. Native plants are not passive. They are resilient and are actively trying to survive. Instead of asking how we can save native species, a better question might be how can we support what native species are already doing. How can human management support native species resilience?