NeighborSpace is proud to present its final report on the historical role of Bear Creek and its people. Principal investigator Dr. Glenn Johnston worked for more than two years with a team of professional historians, community historians, and Stevenson University students to analyze military operations during the War of 1812 and to document the natural and cultural landscape of Patapsco Neck leading up to the War. The full report can be accessed here and print copies will be available for loan soon. Highlights of the study are summarized in these pages.

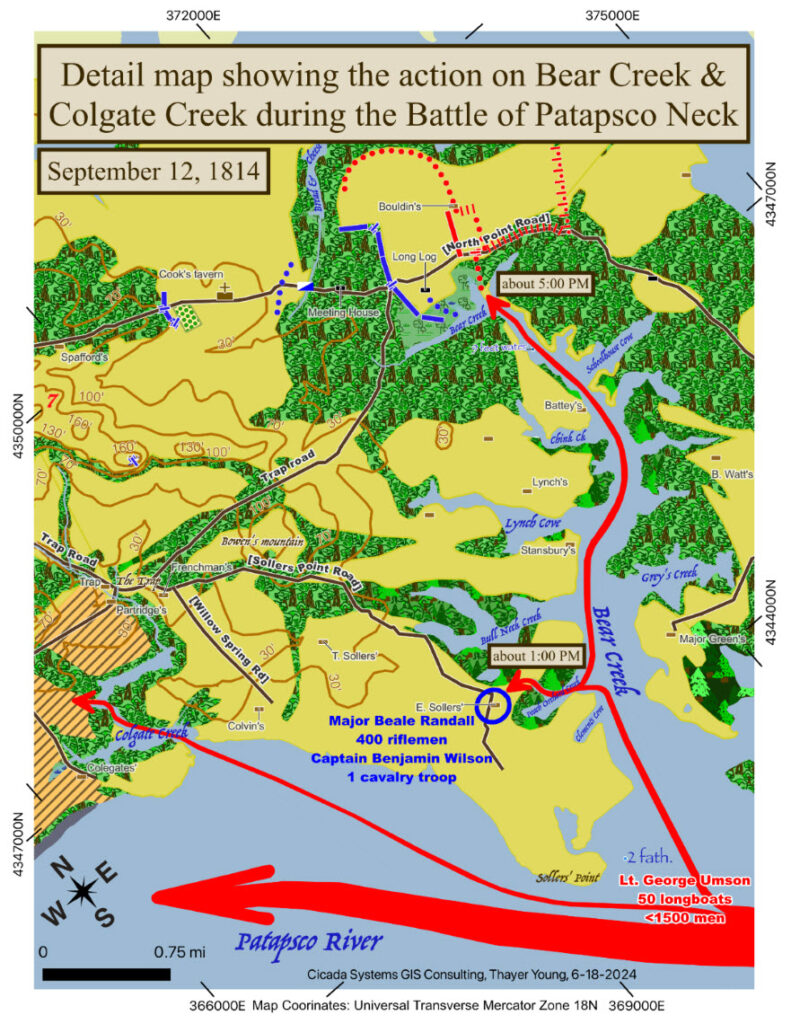

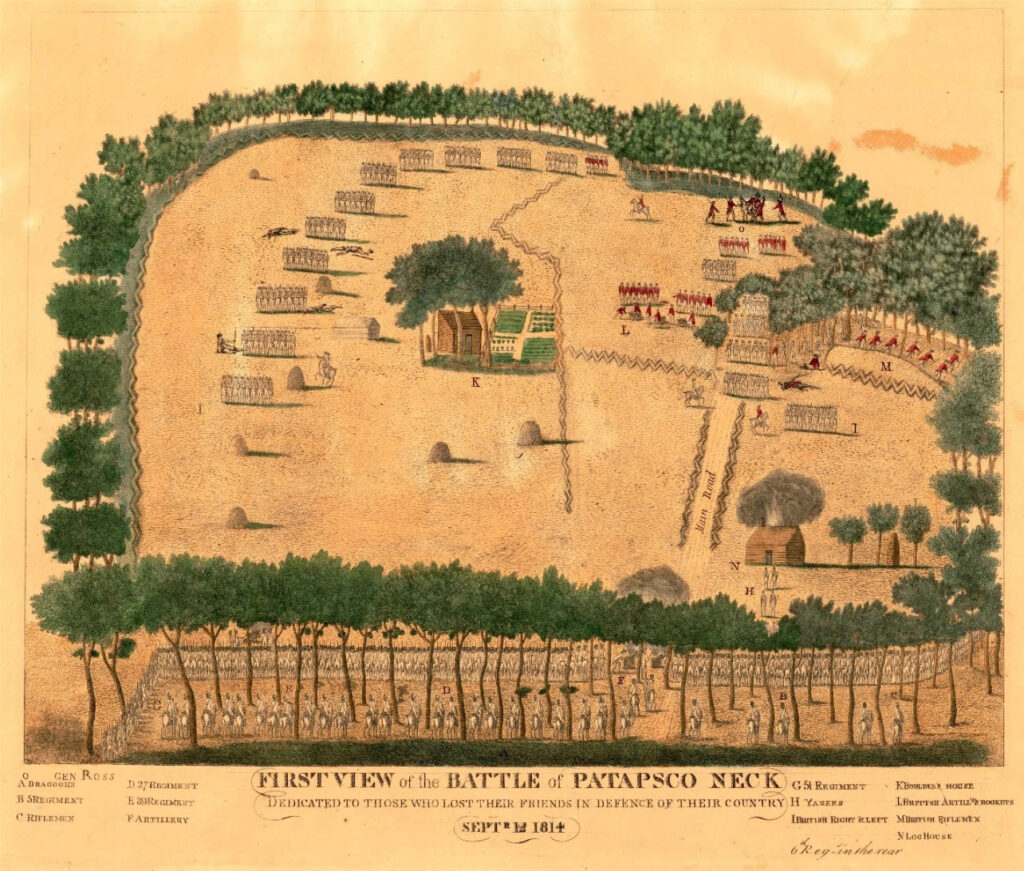

Significant outcomes of the team’s research include an improved and altered understanding of the role of Bear Creek in the defense of Baltimore. Original documents provide evidence that Bear Creek was a piece of key terrain and contributed significantly to the Battle of Patapsco Neck and the land defense of the port of Baltimore. Bear Creek served both as an avenue of approach for the British barges to attack the Americans and as a logistical transportation route for British forces during their attack. A limited but significant engagement at Lower Bear Creek slowed, if not stopped, the British advance. These findings confirm what community members have long thought to be true. Bear Creek was part of the battlefield on which engagements were fought and operations conducted as part of the defense of the port of Baltimore in 1814, and the people of Patapsco Neck were widely represented on its field of battle or performing supporting duties as civilians.

While a study of the Patapsco Neck community was difficult due to the fact that in those times data was gathered for a larger administrative unit (the lower Patapsco Hundred), the research team was able to make the following observations:

- Women were marginalized at the time of the War of 1812 and little evidence of their lives exists. However, the research team was able to develop narratives for three prominent women.

- Native American encampments have been documented in the vicinity of present-day North Point State Park and Bear Creek, and North Point very likely runs along an old Native American trail.

- Many more African Americans lived in the Lower Patapsco Hundred than initially thought. Of the total population recorded in the 1810 census (2,670), 38% were African Americans. Of those residents, only 43% were free, accounting for 51 families. Most of these free Black families lived in six clusters in the Lower Patapsco Hundred.

Unsurprisingly, the natural landscape of Patapsco Neck looked very different at the time of the War of 1812. Much of the area, possibly as much as 50%, consisted of unimproved tree-covered lands. An officer present in the British advance observed that

“The high road wound for many miles through the center of a dark forest; and the course of the flankers was rarely indeed diversified with any other prospect, besides that of an apparently interminable wilderness of trees”.

Today, very little of that green space remains in the Dundalk area, and public access to the waterfront is especially limited. The Bear Creek Heritage Trail will not only share the above history with the public but will provide the community with access to green space along the waterfront. NeighborSpace is currently working with Brenton Landscape Architecture to design Phase 3 of the trail.

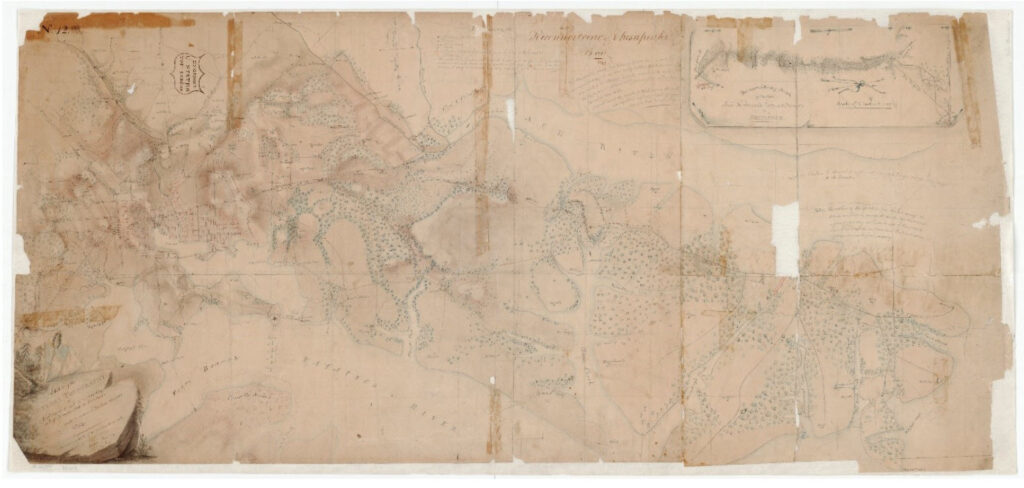

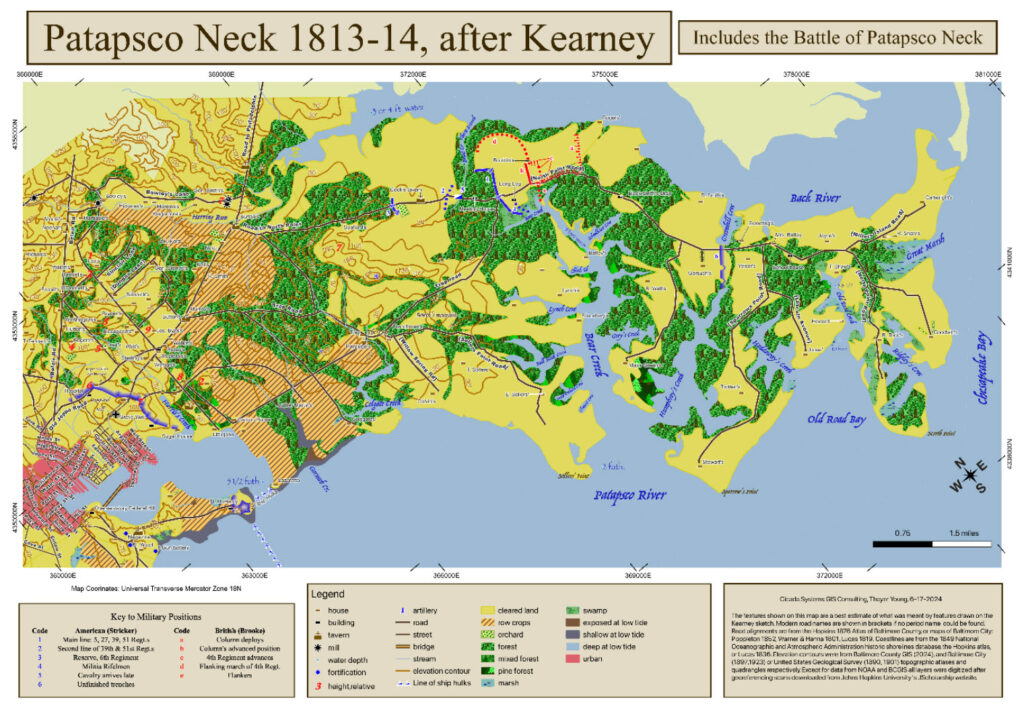

Bottom: The Kearney Map redone on a modern datum representing the actual geography of Patapsco Neck, by Thayer Young.