Bear Creek Historical Project

A Study of the Land and Its People

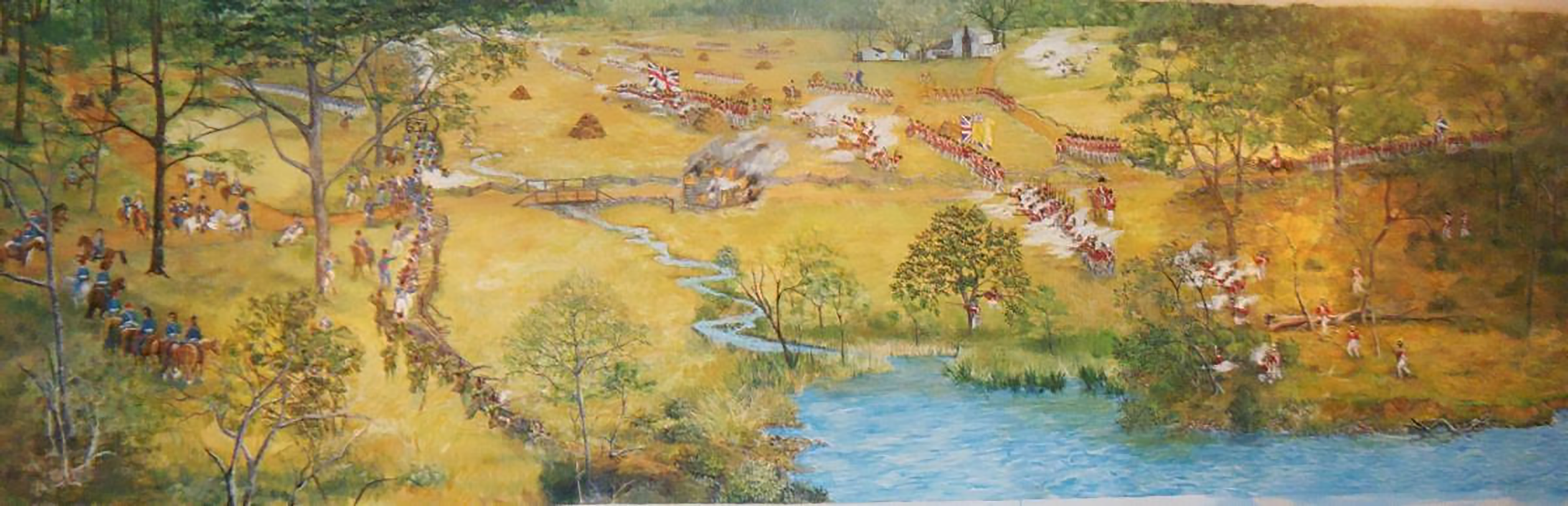

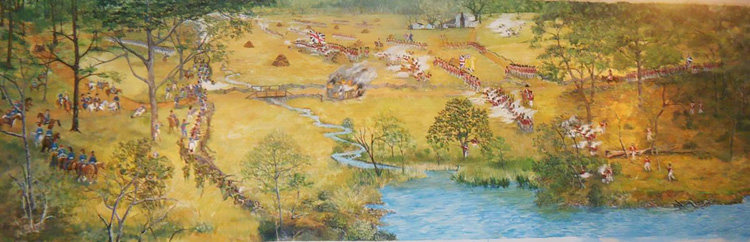

THE BRITISH ATTACK

PREPARATIONS ALONG PATAPSCO NECK PRIOR TO THE BRITISH ATTACK

In February 1814, in the second year of the War of 1812, British ships arrived to blockade Chesapeake Bay and punish the Chesapeake region for its support of the war. A few weeks later, Major General Samuel Smith of Baltimore, a former Revolutionary War officer, local merchant, Congressman, and US Senator, was ordered by Maryland Governor Levin Winder “to make the necessary arrangements for the defense of the port of Baltimore.”

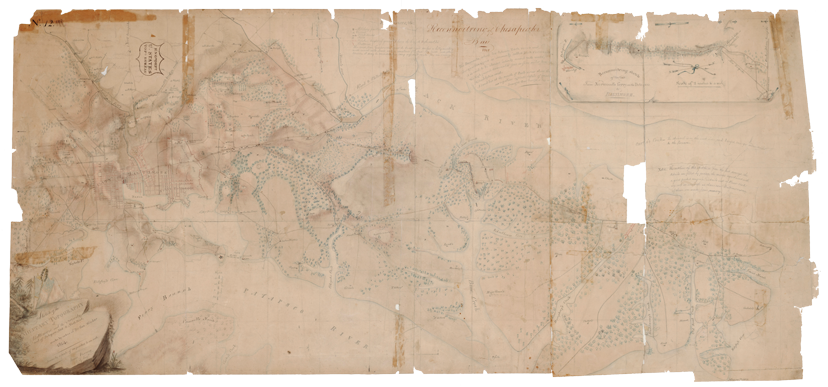

In one of his first acts as commander, Smith ordered Major William B. Barney, a cavalry officer and son of Commodore Joshua Barney, whose family had long lived on Bear Creek, to lead a military reconnaissance of the land lying between Baltimore and the eastern tip of Patapsco Neck at North Point. On March 21, 1813, along with other officers, Barney set out to conduct that survey. His field notes and sketch of that reconnaissance was crucial to General Smith’s plans for Baltimore’s defense.

Analyzing Barney’s reconnaissance report, General Smith observed the many creeks and coves along Patapsco Neck. In particular, he noted two choke points along North Point Road the enemy would need to negotiate in order to advance to Baltimore. One was at the head of Humphrey’s Creek (near Edgemere), and the other at the head of Bear Creek (near what is Battle Acre today). Each of the two choke points would play a part in General Smith’s defensive plans.

It was at this place that General Smith planned to engage in battle with the British. In a brief spirited defense, his troops could bloody the enemy, gain intelligence, and provide his men limited fighting experience before retiring to the main US defenses on Hampstead Hill (Patterson Park) about six miles to its rear.

In the case of the choke point at the head of Humphrey’s Creek (Edgemere today), General Smith realized the North Point Road could be cut by a fortified trench and used as a defensive position by American troops. Anchored on either end by a water feature– Humphrey’s Creek on the American right and Back River on its left– the trench and its defenders would certainly require effort to dislodge by the British. British losses might be high if the American entrenchment was supported by cannon fire. That being said, the entrenchment was simply an obstacle to slow the enemy and chip away at their strength. It would not stop them.

The second choke point, at the head of Bear Creek, held far more value for grinding away at the enemy’s strength. Similar to the land near the head of Humphrey’s Creek, the land at the head of Bear Creek could be turned into a linear defensive position anchored on each end by a water feature. The path along which the British would need to advance was only about 3,500 foot wide and was flanked to their left by the head of Bear Creek and to their right by marshland and Back River. The land consisted largely of flat farm fields. There were few places the British could take cover or hide.

Smith also knew Bear Creek could be a two-edged sword. In 1813, a year before the battle, as he watched the British Navy operating at the mouth of the Patapsco, he noted the speed and maneuverability of the British barges (longboats) that carried up to 50 soldiers, small cannons, and rockets. They took him by surprise. Easily unloaded from British ships, manned by experienced crews, he worried that in any future fight with the British at Bear Creek’s head, British barges might row up Bear Creek from its mouth on the Patapsco and cut off and capture his militiamen before they could return safely to Baltimore. While Bear Creek was an obstacle to the British Army, it was a highway to the British Navy.

In addition to preparing for a battle at the head of Bear Creek, Smith prepared for at least a skirmish at its mouth. During 1813, Smith sent various infantry regiments to encamp at that location, thereby providing experience to his green militia troops in how to protect Bear Creek from an incursion by British longboats.

ACTIONS ON PATAPSCO NECK DURING THE BRITISH ATTACK

On September 11, 1814, the British Chesapeake Bay squadron entered the mouth of the Patapsco River with Baltimore as its target. Landing about 4,500 soldiers, sailors, and marines at North Point on Patapsco Neck’s eastern extremity, elements of the squadron continued to advance up the Patapsco River toward Baltimore. The small army it landed at North Point advanced toward Baltimore along North Point Road. As was their standard procedure, the British Army and Navy advanced parallel to each other, one on land, the other on water.

Warned of the British landing, the Americans – whose main defense was in Baltimore at Hampstead Hill – placed a temporary defensive line at the head of Bear Creek on Patapsco Neck. The American right was anchored on the head of Bear Creek, extended across North Point Road, and anchored its left on the marshy wooded ground near Back River. The American on-site commander, Brigadier General John Stricker, deployed his 3,185 men in three lines at a right angle to the Back River and Patapsco River.

Stricker also deployed 400 riflemen about four miles down Bear Creek near its mouth on Sollers Point at the homestead of Juliet Eliza Sollers. They were to guard against an attack by British longboats that might outflank his army’s right by attacking up Bear Creek. The riflemen were commanded by Major Beale Randall.

As the British army advanced toward Baltimore along North Point Road, it was engaged by a small force of Maryland militia shortly after departing Gorsuch Farm. During that small engagement, at about 1:30 PM on September 12, the British commander, Major General Robert Ross, was shot and mortally wounded. His subordinate, Colonel Arthur Brooke, took over command. They continued their advance along North Point Road.

At about the same time, a division of as many as 50 British longboats entered the mouth of Bear Creek four miles south near the Patapsco River. They carried a landing force of 1,500 men as well as cannons and rockets. Unaware of the battle that would soon occur at the head of Bear Creek, the boats were simply trying to gain control of the creek as a transportation path and communications link between the British Navy on the river and its army on Patapsco Neck. Randall’s riflemen on Soller’s Point were shot at by cannon, Congreve rockets, and small arms fire by the British attackers. The result was a small battle between the British boats and Randall’s riflemen on Soller’s Point. Fearing they would be cut off from other US forces, the American riflemen withdrew toward Colgate Creek nearer Baltimore.

About one and a half hours after the engagement at the mouth of Bear Creek, at approximately 3:00 PM on September 12, US forces and the British fought a pitched battle at the head of Bear Creek. Known at the time as the Battle of Patapsco Neck, it would later gain the name “The Battle of North Point.” After several hours of intense fighting, the US forces withdrew toward Baltimore. Bear Creek was entirely in British hands by sundown on September 12.

A day later, on September 13, as the British moved toward Baltimore, a force of British soldiers set off from the vicinity of Colgate Creek advancing along Patapsco Neck toward Sollers farmstead on Bear Creek. In retribution for the Americans having used the Sollers homestead to attack the British, the British returned to burn that homestead.

On September 14, 1814, with Fort McHenry and Hampstead Hill undefeated, the British, unable to meet their military objectives, withdrew.