Bear Creek Historical Project

A Study of the Land and Its People

THE PEOPLE OF PATAPSCO NECK

NATIVE AMERICANS

Before Europeans arrived, two Native American peoples shared what is now Baltimore County for the purpose of hunting, fishing, gathering, and trade. To the north, in the vicinity of the Susquehanna River, lived the Susquehannock. To the south, near the Potomac River, lived the Piscataway.

The area between the Patuxent River in the south and the Gunpowder River in the north was a shared resource between both the Piscataway and Susquehannock during times of peace. It could be freely transited for trade purposes, hunting, fishing, and gathering. At certain times of the year temporary camps might be set-up, but no evidence suggests that long-term Native American settlements existed in Central Baltimore County or along Patapsco Neck.

SUSQUEHANNOCK

The Susquehannock lived at the northern end of Chesapeake Bay near the Susquehanna River. Known as fierce fighters, they lived within palisaded villages that protected their longhouses. Outside the walls of their villages were fields for maize (corn), beans, and squash. Hunting and fishing provided deer, elk, black bear, fish, freshwater mussels, wild turkey, and waterfowl. Foraging supplemented their diet with wild plants, fruits, and nuts. Traders, they rapidly adjusted to trading furs with Europeans in return for European tools, glass beads, and, later, muskets. Their diet was varied and seasonal.

PISCATAWAY

Farther to the south, the Piscataway people lived along the north bank of the Potomac River. Similar to the Susquehannock, Piscataway villages consisted of several longhouses protected by a log palisade. They relied on agriculture which enabled them to live in permanent villages. Their crops included maize (corn), several varieties of beans, melons, pumpkins, squash, and tobacco, which were cultivated by women. Men hunted bear, elk, deer, and wolves, as well as smaller game such as beaver, squirrels, partridges, and wild turkeys. They also fished and harvested oysters and clams. Women gathered berries, nuts and roots in order to supplement their diet.

NATIVE AMERICAN INFLUENCES ALONG PATAPSCO NECK

The influence of Native Americans on Patapsco Neck’s history lies today in its name and its main road. According to the Maryland State Archives, the Native American meaning of Patapsco is uncertain, but it may reference to the water’s “penetrating a ledge of rock” as it flowed. Another opinion gives “back water,” or “tide-water covered with froth” as the translation for Patapsco. Regardless of its definition, the name has come down from Native American cultures through 400 years of history and continues to be used today. The second influence is North Point Road itself. It is built on top of an old “Indian trail” along the Neck’s spine that Native Americans used to access the rich fishing grounds where the Patapsco River and Chesapeake Bay united.

Evidence that Native Americans visited the coastal area of North Point is supported by projectile points and other stone implements amid piles of oyster shells located two feet under the surface near Todd’s Inheritance.

SETTLERS

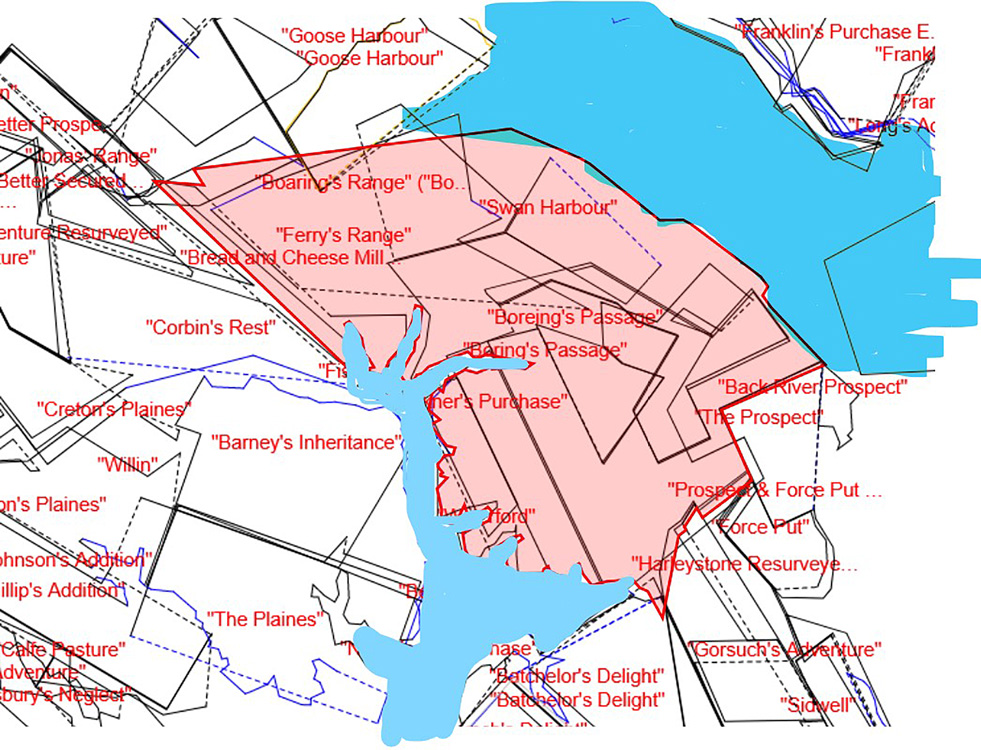

When the King of England granted Maryland to Cecil Calvert and his family in 1632, he gave them ownership of all its lands. With the exception of a short period between 1689-1715, Calvert and his successors had full authority to sell and assign parcels of land as they saw fit. The document that conveyed land from the Lord Proprietor (Calvert) to the new owner was called a land patent, or patent, for short. From these patent records historians can piece together the history of land ownership in the state.

Patapsco Neck began to be settled in the 1650s. While still considered part of Anne Arundel County, in 1652, a land patent was assigned to Thomas Sparrow on Patapsco Neck. He named his patent “Sparrow’s Nest.” Since that time, the name Sparrow has been associated with the part of the Neck near the confluence of Bear Creek and the Patapsco River.

Ralph Williams received a patent for land near the eastern tip of Patapsco Neck in 1665. He named his patent “the North Point.” In 1670, Thomas Todd received a patent for land that he named “Todd’s Range.” The family name is still in use through “Todd’s Inheritance” located on North Point Road. By the time of the War of 1812, about 136 land patents had been granted along Patapsco Neck. Among the family names of owners are those still familiar to us today: Stansbury, Todd, Jones, Gorsuch, Shaw, Lynch, and Sollers.

By 1800, although there were many farms on Patapsco Neck, much of the land was still covered by forest. Land owners were motivated by the tax code to leave much of their land in a virgin state since taxes were not levied on “unimproved” land. Other than farming, by 1798 the tax records show occupations in the area associated with milling, quarrying, brick making, kiln operations, and taverns.

The poorest of the families, both White and Black, were usually tenant farmers (renters) on someone else’s land. They earned their keep by working that land and keeping a small percentage of its produce or profit for themselves. Middle-class families, both White and Black, usually lived on farms they owned, sometimes owned an enslaved person to help in the fields, and often employed free African Americans to work in their kitchen and around the house. The wealthiest families, all White, lived on large plantations and employed large numbers of field workers, servants, and skilled tradespeople, both free and enslaved, both Black and White. Plantation owners often split their time between business pursuits in Baltimore City, public service, and operating their plantations.

(Courtesy of George Washington’s Mount Vernon)

THE BLACK COMMUNITY

Within a few years after Maryland was founded, it had created counties that were subdivided into “Hundreds” for tax and voting purposes. Patapsco Neck was part of the “Lower Patapsco Hundred” that encompassed modern Patapsco Neck, Canton, Govanstown, the Jones Falls area, Towson and the land between them. It did not include Baltimore City. In general, Patapsco Neck was about 10% of the people of the Lower Patapsco Hundred. In 1810, the Lower Patapsco Hundred had a population of about 2,713 of which about 1,658 (61%) were White and 1,055 (39%) Black. Within the Black population, about 339 (43%) were free and about 715 (57%) were enslaved.

About 40% of the families in the Lower Patapsco Hundred were slaveholders. White households owned 94% of the enslaved people and Black households about 6%. It is generally believed by historians that formerly enslaved Black people often worked to purchase their own family members out of slavery. On paper, it would appear as if a free Black “owner” was enslaving other Blacks, when, in fact, they were trying to make them free by purchasing them. In the process, they became slave owners.

The average family size, White or Black, was about 5.5 people. The average residence was only about 450 sq ft in area. That meant the average person living in the Lower Patapsco Hundred in 1810 had about 75 sq ft of living space in their house or cabin. That’s roughly the amount of space allocated to each inmate in a federal prison today.

Because enslaved Black people were considered property under the law, the family structure of enslaved Black people wasn’t recorded in census and tax assessment records. Consequently, although we know there was a family structure among enslaved people, we are unable to reconstruct that structure from existing records.

African Americans, whether free or enslaved, provided a great amount of skilled and unskilled labor within the Patapsco Neck community. Examples exist of both free and enslaved Black people engaged in skilled jobs in the trades, iron forging, lime kiln operations, brick production, shipbuilding, and as house servants. Equally available is evidence showing the employment of both free and enslaved Black people as unskilled and semi-skilled labor in the fields, clearing land, and general construction.

◂ This scene shows a white overseer smoking a pipe and standing on a tree stump over two African American enslaved women who are using garden hoes. They are clearing the land. The trees have been felled, the stumps are being burned and the women are uncovering the roots of the stumps. (Watercolor by Benjamin Henry Latrobe circa 1798, from the Latrobe sketchbooks. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.)