Gwynn Oak Park and the Civil Rights Movement, from the Historical Marker Database

Saturday, October 20, 2024: With funding from MD Humanities and the assistance of community partners, NeighborSpace hosted a free Woodlawn History Bus Tour for more than 50 participants. Read on for more information about the tour's stops!

The Emmart-Pierpont Safe House

Image of the Emmart-Pierpont Safe House sign, courtesy of CCBC Invisible History, The Emmart-Pierpont Safe House

"“It’s phenomenal that it’s right here...it’s too bad it isn’t a little more well-known,” Mia Woods, a 39-year-old social worker, noted in a 2011 Baltimore Sun article on the Emmart-Pierpont Safe House, a landmark of Baltimore County. A strange-looking house, painted white with a red roof, the Emmart-Pierpont Safe House is found on Rolling Road in Rockdale, near Randallstown, and, according to the Sun article, is the only recorded safe house for the enslaved in Baltimore County. The safe house was an Underground Railroad station: a safe shelter for the enslaved to rest and eat.

Built in 1791, withstanding every presidency within the country, the safe house was owned by a farmer and Underground Railroad stationmaster named Caleb Emmart. In his life, Emmart married a woman named Susannah Zimmerman who was an abolitionist along with her sister Elizabeth who was married to Nicholas Smith, a conductor on the Underground Railroad. Together, the four helped enslaved runaways. In the 1800s, Emmart and his family opened their home, the present-day Emmart-Pierpont Safe House, to enslaved runaways who were seeking shelter before continuing their path to freedom."

[CCBC Invisible History, The Emmart-Pierpont Safe House]

Mt. Olive Cemetery - 5115 Old Court Rd

Photo credit: Phyllis Joris

Mount Olive Cemetery is where, among others, the Emmart family are buried. Pictured is the grave of Susannah Emmart, abolitionist and one of the founders of the Emmart-Pierpont Safe House.

Emmarts United Methodist Church

Photo credit: Phyllis Joris

Next, the group stopped at Emmarts United Methodist Church, for which Caleb Emmart donated the land. It is said that the Church also served as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

The Site of Gwynn Oak Amusement Park

Image of July 1963 protest at Gwynn Oak Amusement Park, courtesy of Gwynn Oak Park: A Civil Rights Movement in Baltimore from Studies in Feminist Activism by UMBC

"Gwynn Oak Amusement Park was one of many fun parks in the Baltimore area. The park brought in guests with fun attractions like bumper cars, a wooden roller coaster, a merry-go-round, a giant ferris wheel, and of course rigged carnival games. The park was very popular, did well financially, and was open for about 80 years. The park was a constant in the community, and was enjoyed by many. The first years, however, allowed only white guests into the park. The park owners, the Price family, claimed that desegregating the park would put their white customers safety and satisfaction of the park at risk, and refused to desegregate.

On July 4th, 1963, the protests of Gwynn Oak Amusement Park began and were highly publicized. Protesters included locals of the community, church members, and even people from other states, all of multiple races and religious affiliations. While nearly 300 of the protesters on July 4th were arrested, almost all were exposed to confrontation, hurtful and abusive language, and assault. A few days later on July 7, even more protests against the amusement park took place. The protests were now receiving national attention and protesters were growing by the day. The voices of the protesters were finally heard, and the Prices decided that they would desegregate the park."

[Gwynn Oak Park: A Civil Rights Movement in Baltimore from Studies in Feminist Activism by UMBC]

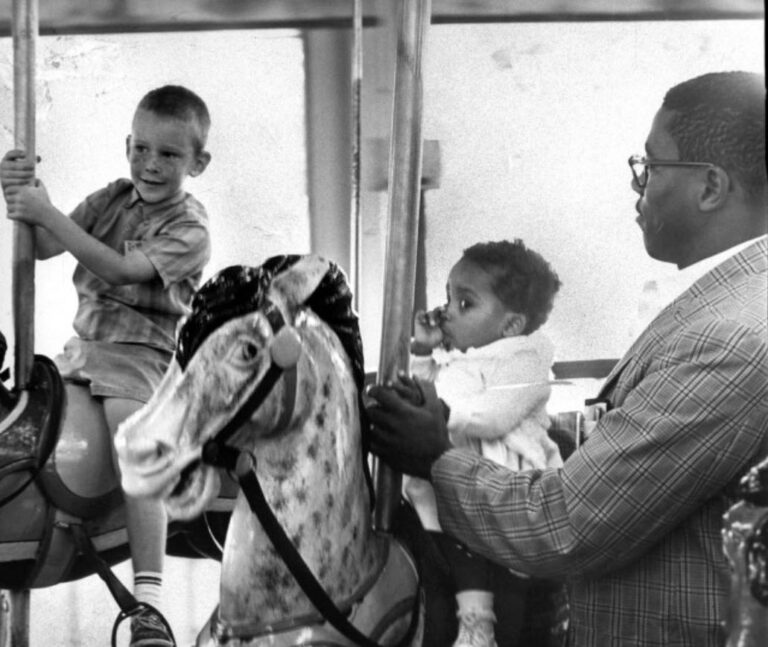

Charles Langley holds his daughter, Sharon, the first African American to ride at the Gwynn Oak Park, August 28, 1963. Original Source: Baltimore Sun. [Zinn Education Project]

"On August 28, 1963 Gwynn Oak opened their desegregated doors to the community, and guests of all races and religions flooded into the park. History was made in Baltimore on this day as 11-month-old Sharon Langley was the first African American child to ride the merry-go-round at the amusement park.

Today, a city park open to the community occupies the location of the old amusement park. On site is a plaque commemorating the site, the activism that took place, and the progression that has been made in the civil rights movement."

[Gwynn Oak Park: A Civil Rights Movement in Baltimore from Studies in Feminist Activism by UMBC]

Legacy Awards (formerly Joe Manns Awards)

Photo credit: Phyllis Joris

The final stop on the tour was Legacy Awards (formerly Joe Manns Awards) to visit a display set up by the Hubert V. Simmons Museum of Negro Leagues Baseball. The Negro Leagues in Woodlawn were part of the broader Negro League baseball system, providing Black athletes the opportunity to showcase their talent during segregation. These leagues played a key role in both the local community and the larger struggle for racial equality, helping pave the way for the integration of Major League Baseball. Co-founder Ray Banks and his colleagues presented information about women in the Negro Leagues and shared stories of individual players.

Resources

-

Allana Therese Calahatian, The Emmart-Pierpont Safe House, CCBC Invisible History

-

Linda Worthington, Runaway Slaves found refuge at Emmarts UMC, Baltimore-Washington Conference of The United Methodist Church Online Archives

-

The Afro July 9, 1963, Mabel Grant, Lydia Wilkins

-

Emmanuel Mehr, Rethinking Baltimore’s July Fourth: Anti-Segregation Protests at Gwynn Oak Amusement Park, 1963, Baltimore Histories Weekly

-

Gwynn Oak Park, Wikipedia

-

Reginald F. Lewis Museum, Oral History at the Lewis – Charles Mason

-

Hubert V. Simmons Museum of Negro Leagues Baseball

-

Freedom Trail

-

Baltimore County Lynching Memorial Project